The Vatican: City, City-State, Nation, or … Bank?

Many think of Vatican City only as the seat of governance for the world’s 1.3 billion Roman Catholics. Atheist critics view it as a capitalist holding company with special privileges. However, that postage-stamp parcel of land in the center of Rome is also a sovereign nation. It has diplomatic embassies—so-called apostolic nunciatures—in over 180 countries, and has permanent observer status at the United Nations.

Only by knowing the history of the Vatican’s sovereign status is it possible to understand how radically different it is compared to other countries. For over 2,000 years the Vatican has been a nonhereditary monarchy. Whoever is Pope is its supreme leader, vested with sole decision-making authority over all religious and temporal matters. There is no legislature, judiciary, or any system of checks and balances. Even the worst of Popes—and there have been some truly terrible ones—are sacrosanct. There has never been a coup, a forced resignation, or a verifiable murder of a Pope. In 2013, Pope Benedict became the first pope to resign in 600 years. Problems of cognitive decline get swept under the rug. In its unchecked power of a single man, the Vatican is closest in its governance style to a handful of absolute monarchies such as Saudi Arabia, Brunei, Oman, Qatar, and the UAE.

During the Renaissance, Popes were feared rivals to Europe’s most powerful monarchies.

From the 8th century until 1870 the Vatican was a semifeudal secular empire called the Papal States that controlled most of central Italy. During the Renaissance, Popes were feared rivals to Europe’s most powerful monarchies. Popes believed God had put them on earth to reign over all other worldly rulers. The Popes of the Middle Ages had an entourage of nearly a thousand servants and hundreds of clerics and lay deputies. That so-called Curia—referring to the court of a Roman emperor—became a Ladon-like network of intrigue and deceit composed largely of (supposedly) celibate single men who lived and worked together at the same time they competed for influence with the Pope.

The cost of running the Papal States, while maintaining one of Europe’s grandest courts, kept the Vatican under constant financial strain. Although it collected taxes and fees, had sales of produce from its agriculturally rich northern region, and rents from its properties throughout Europe, it was still always strapped for cash. The church turned to selling so-called indulgences, a sixth-century invention whereby the faithful paid for a piece of paper that promised that God would forgo any earthly punishment for the buyer’s sins. The early church’s penances were often severe, including flogging, imprisonment, or even death. Although some indulgences were free, the best ones—promising the most redemption for the gravest sins—were expensive. The Vatican set prices according to the severity of the sin.

The Church had to twice borrow from the Rothschilds.

All the while, the concept of a budget or financial planning was anathema to a succession of Popes. The humiliating low point came when the Church had to twice borrow from the Rothschilds, Europe’s preeminent Jewish banking dynasty. James de Rothschild, head of the family’s Paris-based headquarters, became the official Papal banker. By the time the family bailed out the Vatican, it had only been thirty-five years since the destabilizing aftershocks from the French Revolution had led to the easing of harsh, discriminatory laws against Jews in Western Europe. It was then that Mayer Amschel, the Rothschild family patriarch, had walked out of the Frankfurt ghetto with his five sons and established a fledgling bank. Little wonder the Rothschilds sparked such envy. By the time Pope Gregory asked for the first loan they had created the world’s biggest bank, ten times larger than their closest rival.

The Vatican’s institutional resistance to capitalism was a leftover of Middle Age ideologies, a belief that the church alone was empowered by God to fight Mammon, a satanic deity of greed. Its ban on usury—earning interest on money loaned or invested—was based on a literal biblical interpretation. The Vatican distrusted capitalism since it thought secular activists used it as a wedge to separate the church from an integrated role with the state. In some countries, the “capitalist bourgeoisie”—as the Vatican dubbed it—had even confiscated church land for public use. Also fueling the resistance to modern finances was the view that capitalism was mostly the province of Jews. Church leaders may not have liked the Rothschilds, but they did like their cash.

The Church’s sixteen thousand square miles was reduced to a tiny parcel of land.

In 1870, the Vatican lost its earthly empire overnight when Rome fell to the nationalists who were fighting to unify Italy under a single government. The Church’s sixteen thousand square miles was reduced to a tiny parcel of land. The loss of its Papal States income meant the church was teetering on the verge of bankruptcy.

The Vatican survived going forward on something called Peter’s Pence, a fundraising practice that had been popular a thousand years earlier with the Saxons in England (and later banned by Henry VIII when he broke with Rome and declared himself head of the Church of England). The Vatican pleaded with Catholics worldwide to contribute money to support the Pope, who had declared himself a prisoner inside the Vatican and refused to recognize the new Italian government’s sovereignty over the Church.

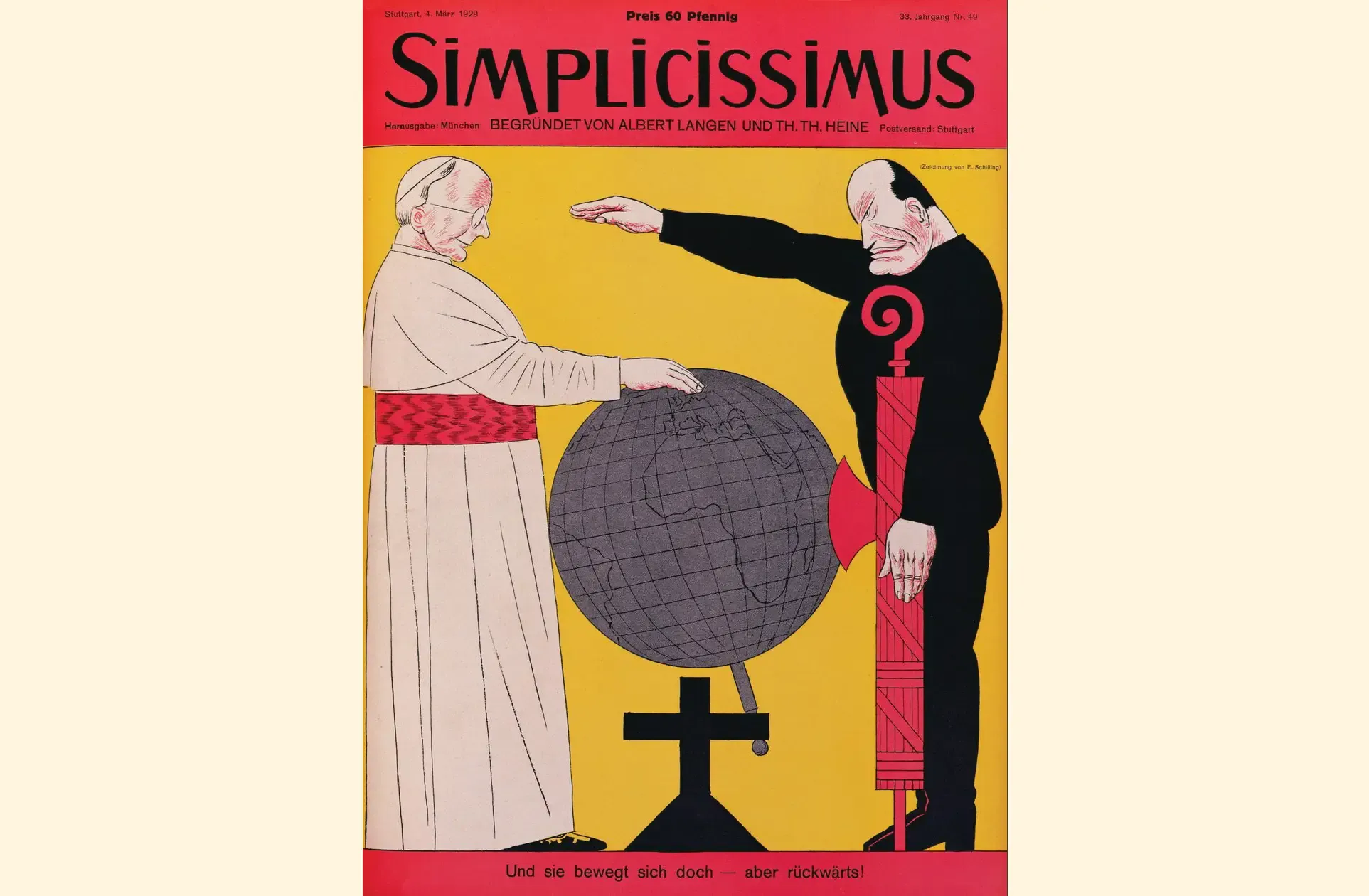

During the nearly 60-year stalemate that followed, the Vatican’s insular and mostly incompetent financial management kept it under tremendous pressure. The Vatican would have gone bankrupt if Mussolini had not saved it. Il Duce, Italy’s fascist leader, was no fan of the Church, but he was enough of a political realist to know that 98 percent of Italians were Catholics. In 1929, the Vatican and the Fascist government executed the Lateran Pacts. It gave the Church the most power since the height of its temporal kingdom. It set aside 108.7 acres as Vatican City and fifty-two scattered “heritage” properties as an autonomous neutral state. It reinstated Papal sovereignty and ended the Pope’s boycott of the Italian state.

The settlement—worth about $1.6 billion in 2025 dollars—was approximately a third of Italy’s entire annual budget.

The Lateran Pacts declared the Pope was “sacred and inviolable,” the equivalent of a secular monarch, and acknowledged he was invested with divine rights. A new Code of Canon Law made Catholic religious education obligatory in state schools. Cardinals were invested with the same rights as princes by blood. All church holidays became state holidays and priests were exempted from military and jury duty. A three-article financial convention granted “ecclesiastical corporations” full tax exemptions. It also compensated the Vatican for the confiscation of the Papal States with 750 million lire in cash and a billion lire in government bonds that paid 5 percent interest. The settlement—worth about $1.6 billion in 2024 dollars—was approximately a third of Italy’s entire annual budget and a desperately needed lifeline for the cash-starved church.

Pius XI, the Pope who struck the deal with Mussolini, was savvy enough to know that he and his fellow cardinals needed help managing the enormous windfall. He therefore brought in a lay outside advisor, Bernardino Nogara, a devout Catholic with a reputation as a financial wizard.

Nogara took little time in upending hundreds of years of tradition. He ordered, for instance, that every Vatican department produce annual budgets and issue monthly income and expense statements. The Curia bristled when he persuaded Pius to cut employee salaries by 15 percent. And after the 1929 stock market crash, Nogara made investments in blue-chip American companies whose stock prices had plummeted. He also bought prime London real estate at fire-sale prices. As tensions mounted in the 1930s, Nogara further diversified the Vatican’s holdings in international banks, U.S. government bonds, manufacturing companies, and electric utilities.

Only seven months before the start of World War II, the church got a new Pope, Pius XII, one who had a special affection for Germany (he had been the Papal Nuncio—ambassador—to Germany). Nogara warned that the outbreak of war would greatly test the financial empire he had so carefully crafted over a decade. When the hot war began in September 1939, Nogara realized he had to do more than shuffle the Vatican’s hard assets to safe havens. He knew that beyond the military battlefield, governments fought wars by waging a broad economic battle to defeat the enemy. The Axis powers and the Allies imposed a series of draconian decrees restricting many international business deals, banning trading with the enemy, prohibiting the sale of critical natural resources, and freezing the bank accounts and assets of enemy nationals.

The United States was the most aggressive, searching for countries, companies, and foreign nationals who did any business with enemy nations. Under President Franklin Roosevelt’s direction, the Treasury Department created a so-called blacklist. By June 1941 (six months before Pearl Harbor and America’s official entry into the war), the blacklist included not only the obvious belligerents such as Germany and Italy, but also neutral nations such as Switzerland, and the tiny principalities of Monaco, San Marino, Liechtenstein, and Andorra. Only the Vatican and Turkey were spared. The Vatican was the only European country that proclaimed neutrality that was not placed on the blacklist.

There was a furious debate inside the Treasury department about whether Nogara’s shuffling and masking of holding companies in multiple European and South American banking jurisdictions was sufficient to blacklist the Vatican. It was only a matter of time, concluded Nogara, until the Vatican was sanctioned.

The Vatican Bank could operate anywhere worldwide, did not pay taxes … disclose balance sheets, or account to any shareholders.

Every financial transaction left a paper trail through the central banks of the Allies. Nogara needed to conduct Vatican business in secret. The June 27, 1942, formation of the Istituto per le Opere di Religione (IOR)—the Vatican Bank—was heaven sent. Nogara drafted a chirograph (a handwritten declaration), a six-point charter for the bank, and Pius signed it. Since its only branch was inside Vatican City—which, again, was not on any blacklist—the IOR was free of any wartime regulations. The IOR was a mix between a traditional bank like J. P. Morgan and a central bank such as the Federal Reserve. The Vatican Bank could operate anywhere worldwide, did not pay taxes, did not have to show a profit, produce annual reports, disclose balance sheets, or account to any shareholders. Located in a former dungeon in the Torrione di Nicoló V (Tower of Nicholas V), it certainly did not look like any other bank.

The Vatican Bank was created as an autonomous institution with no corporate or ecclesiastical ties to any other church division or lay agency. Its only shareholder was the Pope. Nogara ran it subject only to Pius’s veto. Its charter allowed it “to take charge of, and to administer, capital assets destined for religious agencies.” Nogara interpreted that liberally to mean that the IOR could accept deposits of cash, real estate, or stock shares (that expanded later during the war to include patent royalty and reinsurance policy payments).

Many nervous Europeans were desperate for a wartime haven for their money. Rich Italians, in particular, were anxious to get cash out of the country. Mussolini had decreed the death penalty for anyone exporting lire from Italian banks. Of the six countries that bordered Italy, the Vatican was the only sovereignty not subject to Italy’s border checks. The formation of the Vatican Bank meant Italians needed only a willing cleric to deposit their suitcases of cash without leaving any paper trail. And unlike other sovereign banks, the IOR was free of any independent audits. It was required—supposedly to streamline recordkeeping—to destroy all its files every decade (a practice it followed until 2000). The IOR left virtually nothing by which postwar investigators could determine if it was a conduit for shuffling wartime plunder, held accounts, or money that should be repatriated to victims.

The Vatican immediately dropped off the radar of U.S. and British financial investigators.

The IOR’s creation meant the Vatican immediately dropped off the radar of U.S. and British financial investigators. It allowed Nogara to invest in both the Allies and the Axis powers. As I discovered in research for my 2015 book about church finances, God’s Bankers: A History of Money and Power at the Vatican, Nogara’s most successful wartime investment was in German and Italian insurance companies. The Vatican earned outsized profits when those companies escheated the life insurance policies of Jews sent to the death camps and converted the cash value of the policies.

After the war, the Vatican claimed it had never invested or made money from Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy. All its wartime investments and money movements were hidden by Nogara’s impenetrable Byzantine offshore network. The only proof of what happened was in the Vatican Bank archives, sealed to this day. (I have written opinion pieces in The New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, calling on the church to open its wartime Vatican Bank files for inspection. The Church has ignored those entreaties.)

Its ironclad secrecy made it a popular postwar offshore tax haven for wealthy Italians wanting to avoid income taxes.

While the Vatican Bank was indispensable to the church’s enormous wartime profits, the very features—no transparency or oversight, no checks and balances, no adherence to international banking best practices—became its weakness going forward. Its ironclad secrecy made it a popular postwar offshore tax haven for wealthy Italians wanting to avoid income taxes. Mafia dons cultivated friendships with senior clergy and used them to open IOR accounts under fake names. Nogara retired in the 1950s. The laymen who had been his aides were not nearly as clever or imaginative as was he. It opened the Vatican Bank to the influence of lay bankers. One, Michele Sindona, was dubbed by the press as “God’s Banker” in the mid-1960s for the tremendous influence and deal making he had with the Vatican Bank. Sindona was a flamboyant banker whose investment schemes always pushed against the letter of the law. (Years later he would be convicted of massive financial fraud and murder of a prosecutor and would himself be killed in an Italian prison.)

Exacerbating the bad effect of Sindona directing church investments, the Pope’s pick to run the Vatican Bank in the 1970s was a loyal monsignor, Chicago-born Paul Marcinkus. The problem was that Marcinkus knew almost nothing about finances or running a bank. He later told a reporter that when he got the news that he would oversee the Vatican Bank, he visited several banks in New York and Chicago and picked up tips. “That was it. What kind of training you need?” He also bought some books about international banking and business. One senior Vatican Bank official worried that Marcinkus “couldn’t even read a balance sheet.”

Marcinkus allowed the Vatican Bank to become more enmeshed with Sindona, and later another fast-talking banker, Roberto Calvi. Like Sindona, Calvi would also later be on the run from a host of financial crimes and frauds, but he never got convicted. He was instead found hanging in 1982 under London’s Blackfriars Bridge.

“You can’t run the church on Hail Marys.” —Vatican Bank head Paul Marcinkus, defending the Bank’s secretive practices in the 1980s.

By the 1980s the Vatican Bank had become a partner in questionable ventures in offshore havens from Panama and the Bahamas to Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and Switzerland. When one cleric asked Marcinkus why there was so much mystery about the Vatican Bank, Marcinkus dismissed him saying, “You can’t run the church on Hail Marys.”

All the secret deals came apart in the early 1980s when Italy and the U.S. opened criminal investigations on Marcinkus. Italy indicted him but the Vatican refused to extradite him, allowing Marcinkus instead to remain in Vatican City. The standoff ended when all the criminal charges were dismissed and the church paid a stunning $244 million as a “voluntary contribution” to acknowledge its “moral involvement” with the enormous bank fraud in Italy. (Marcinkus returned a few years later to America where he lived out his final years at a small parish in Sun City, Arizona.)

Throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s, the Vatican Bank remained an offshore bank in the heart of Rome.

It would be reasonable to expect that after having allowed itself to be used by a host of fraudsters and criminals, the Vatican Bank cleaned up its act. It did not, however. Although the Pope talked a lot about reforms, it kept the same secret operations, expanding even into massive offshore deposits disguised as fake charities. The combination of lots of money, much of it in cash, and no oversight, again proved a volatile mixture. Throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s, the Vatican Bank remained an offshore bank in the heart of Rome. It was increasingly used by Italy’s top politicians, including prime ministers, as a slush fund for everything from buying gifts for mistresses to paying off political foes.

Italy’s tabloids, and a book in 2009 by a top investigative journalist Gianluigi Nuzzi, exposed much of the latest round of Vatican Bank mischief. It was not, however, the public shaming of “Vatileaks” that led to any substantive reforms in the way the Church ran its finances. Many top clerics knew that as a 2,000-year-old institution, if they waited patiently for the public outrage to subside, the Vatican Bank could soon resume its shady dealings.

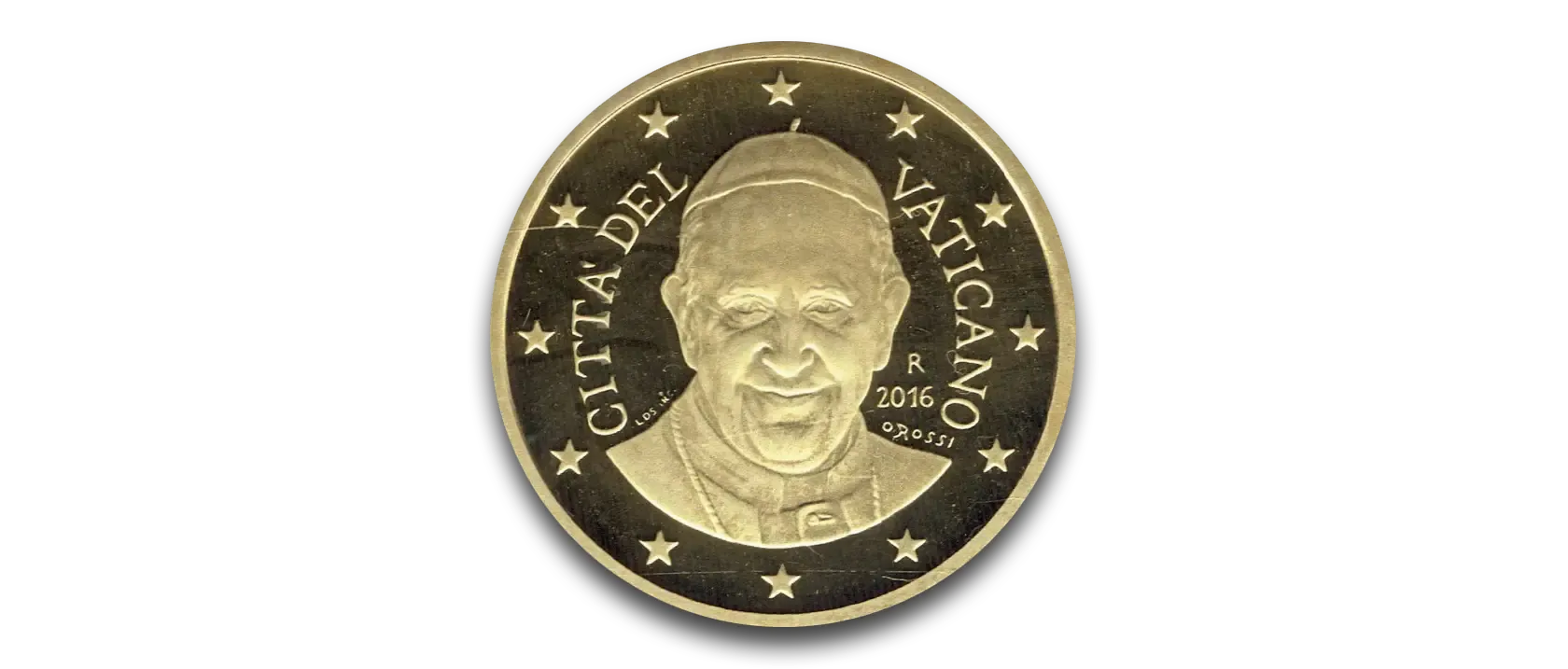

In 2000, the Church signed a monetary convention with the European Union by which it could issue its own euro coins.

What changed everything in the way the Church runs its finances came unexpectedly in a decision about a common currency—the euro—that at the time seemed unrelated to the Vatican Bank. Italy stopped using the lira as its currency and adopted the euro in 1999. That initially created a quandary for the Vatican, which had always used the lira as its currency. The Vatican debated whether to issue its own currency or to adopt the euro. In December 2000, the church signed a monetary convention with the European Union by which it could issue its own euro coins (distinctively stamped with Città del Vaticano) as well as commemorative coins that it marked up substantially to sell to collectors. Significantly, that agreement did not bind the Vatican, or two other non-EU nations that had accepted the euro—Monaco and Andorra—to abide by strict European statutes regarding money laundering, antiterrorism financing, fraud, and counterfeiting.

What the Vatican did not expect was that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a 34-nation economics and trade group that tracks openness in the sharing of tax information between countries, had at the same time begun investigating tax havens. Those nations that shared financial data and had in place adequate safeguards against money laundering were put on a so-called white list. Those that had not acted but promised to do so were slotted onto the OECD’s gray list, and those resistant to reforming their banking secrecy laws were relegated to its blacklist. The OECD could not force the Vatican to cooperate since it was not a member of the European Union. However, placement on the blacklist would cripple the Church’s ability to do business with all other banking jurisdictions.

The biggest stumbling block to real reform is that all power is still vested in a single man.

In December 2009, the Vatican reluctantly signed a new Monetary Convention with the EU and promised to work toward compliance with Europe’s money laundering and antiterrorism laws. It took a year before the Pope issued a first ever decree outlawing money laundering. The most historic change took place in 2012 when the church allowed European regulators from Brussels to examine the Vatican Bank’s books. There were just over 33,000 accounts and some $8.3 billion in assets. The Vatican Bank was not compliant on half of the EU’s forty-five recommendations. It had done enough, however, to avoid being placed on the blacklist.

In its 2017 evaluation of the Vatican Bank, the EU regulators noted the Vatican had made significant progress in fighting money laundering and the financing of terrorism. Still, changing the DNA of the finances of the Vatican has proven incredibly difficult. When a reformer, Argentina’s Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, became Pope Francis in 2013, he endorsed a wide-ranging financial reorganization that would make the church more transparent and bring it in line with internationally accepted financial standards and practices. Most notable was that Francis created a powerful financial oversight division and put Australian Cardinal George Pell in charge. Then Pell had to resign and return to Australia where he was convicted of child sex offenses in 2018. By 2021, the Vatican began the largest financial corruption trial in its history, even including the indictment of a cardinal for the first time. The case floundered, however, and ultimately revealed that the Vatican’s longstanding self-dealing and financial favoritism had continued almost unabated under Francis’s reign.

It seems that for every step forward, somehow, the Vatican manages to move backwards when it comes to money and good governance. For those of us who study it, while it is a more compliant and normal member of the international community today than at any time in its past, the biggest stumbling block to real reform is that all power is still vested in a single man that the Church considers the Vicar of Christ on earth.

The Catholic Church considers the reigning pope to be infallible when speaking ex cathedra (literally “from the chair,” that is, issuing an official declaration) on matters of faith and morals. However, not even the most faithful Catholics believe that every Pope gets it right when it comes to running the Church’s sovereign government. No reform appears on the horizon that would democratize the Vatican. Short of that, it is likely there will be future financial and power scandals, as the Vatican struggles to become a compliant member of the international community.